The modern Catholic geocentrist position isn’t first and foremost derived from an impartial examination of the physical evidence of the cosmos. It’s fundamentally derived from a perception that the Catholic Church has officially endorsed geocentrism as a doctrine of the faith, coupled with an allegedly literal approach to sacred Scripture. I’ve already written extensively to demonstrate that the Catholic Church has never advanced geocentrism as a doctrine of the faith. This essay will focus on the pitfalls we encounter when embracing such an over-literal view of the Bible.

Physicist Phil Plait has alleged concerning geocentrism that, “Finding passages in the Bible to support this belief isn’t hard; Genesis is loaded with them.” But very interestingly, geocentrist Bob Sungenis made this revealing reply: “Actually, Genesis has very few. Most are in the Psalms” (“Reply to Discover Magazine’s Critique of Geocentrism”, p. 2.) This is a crucial admission. Sungenis has openly admitted that the majority of the scriptural “support” for a scientific viewpoint on cosmology is found in a collection of poems. It seems odd to have to point this out, but a poem is probably the last place one should go to discover literal, scientific details about the physical universe. But Sungenis is quite serious in his claim and he wants us to know that he has done a lot of “exegesis” on these passages to back this up:

all these explanations are included in Galileo Was Wrong: The Church Was Right. I have over 50 pages of exegesis on these Scriptural passages. (“Response to David Palm on the Galileo Issue”, p. 41.)

Sungenis has expended a great deal of effort cultivating an image of himself as an accomplished biblical scholar and exegete. But it’s important to remember that when he has a deeply held ideological agenda—as he does with regard to Jews and geocentrism, for example—he’s repeatedly demonstrated a willingness to say almost anything to bolster his case, no matter how ridiculous. And he typically makes his case with such complete assurance and insistence that many people make the mistake of accepting it at face value.

In regard to our present topic, a close analysis of Sungenis’ treatment of what he considers to be the most important psalm for his case (Psalm 19) will illustrate a number of things—the pitfalls of trying to derive physical details from a poem, Sungenis’ limitations as a biblical exegete, as well as a propensity to contradict himself and advance complete nonsense with unshaken conviction.

To set the stage for our examination, here’s the whole passage:

The heavens are telling the glory of God; and the firmament proclaims his handiwork.

Day to day pours forth speech, and night to night declares knowledge.

There is no speech, nor are there words; their voice is not heard;

yet their voice goes out through all the earth, and their words to the end of the world. In them he has set a tent for the sun,

which comes forth like a bridegroom leaving his chamber, and like a strong man runs its course with joy.

Its rising is from the end of the heavens, and its circuit to the end of them; and there is nothing hid from its heat.

In my article “Pope Leo XIII On Literal Interpretation and the Unanimous Consent of the Fathers” I pointed out that this is obviously phenomenological language, that is, it is picturesque, subjective language that describes things in terms of how they appear to us, not in terms of their literal, objective, physical detail:

Both the geocentrist and non-geocentrist agree that these passages are not to be taken literally, but represent the language of appearances, the phenomena that were visible to the observers. But once the geocentrist admits this, he can no longer appeal to these passages as if they literally describe the underlying physical phenomena. And once they no longer literally describe physical phenomena, then no case can be made from them concerning “the essential nature of the things of the visible universe” nor can any claim be made to Leo XIII’s dictum concerning the literal sense of Scripture.

And interestingly, Sungenis himself agrees with my fundamental contention that no objective, physical, scientific details can be gleaned from a purely phenomenological text. He said this in his book Galileo Was Wrong (henceforth GWW):

the most important fact that is invariably missed by modern biblical exegetes who advocate heliocentrism is that Scripture’s phenomenal language (e.g., the “sun rises” or the “sun sets”) also applies to the geocentric system. In the geocentric system the sun does not “rise” or “set”; rather, it revolves around the Earth. When the geocentrist sees a beautiful sunset he does not remark: “Oh, what a beautiful revolution of the sun,” just as the heliocentrist does not say: “Oh, what a beautiful rotation of the Earth.” The geocentrist knows that the sun “rises” or “sets” only with respect to the Earth’s horizon, and therefore, reference to a “rising sun” in Scripture is just as phenomenal in the geocentric system as it is in the heliocentric (GWW1, p. 226; emphasis mine).

The point of this current essay is to demonstrate that the whole context and many specific details demonstrate that Psalm 19:1-6 is phenomenological through and through. Specifically, it’s a metaphorical description of sunrise and sunset. I’ll highlight a number of details that will become important as we examine how Sungenis has mishandled this text. Given his admission above, I think it will become clear why he works so hard to find something, anything in these verses that he can contend is literal and not phenomenological.

The theme of the passage is introduced broadly in verse 1, “The heavens are telling the glory of God; and the firmament proclaims his handiwork” and then made more specific in verse 2, “Day to day pours forth speech, and night to night declares knowledge.” Immediately we recognize that we are in the realm of metaphor—the heavens do not literally “tell”, nor does the firmament “declare”, anything. Days do not speak, nights do not declare knowledge. “Day to day” clearly indicates that the psalmist has in view a daily timeframe in this verse. Then the focus of these metaphors narrows even more to describe the sunrise and sunset, cast in obviously metaphorical/phenomenological language.

Verse 4 states that in the heavens God, “has set a tent for the sun,” and even Sungenis has had to admit that this is clearly metaphorical and not literal. Next the psalmist says that the sun, “comes forth like a bridegroom leaving his chamber.” There are a couple of interesting nuances here. The Hebrew word יָצָא (yâtsâ’, “comes forth”) carries the nuance of coming forth from a starting point—the scholarly Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew lexicon defines the word as, “to go out, come out, exit, go forth.” The obvious starting point here would be the horizon. And this is further bolstered by the metaphor of the bridegroom coming forth from his bedchamber, again a clear allusion to the morning and hence to the sunrise.

Next the sun is said to be, “like a strong man [who] runs its course with joy.” Attribution of emotions to the sun reminds us that we are still firmly in the realm of metaphor. The image of a vigorous and swiftly running strong man indicates again that the poet is speaking of the daylight hours, of a swift passage that has a beginning and an end – sunrise and sunset. It hopefully goes without saying that the sun does not literally have a tent in the sky, does not literally run, does not literally rejoice. And the metaphorical language continues.

Next we read that, “Its rising is from the end of the heavens, and its circuit to the end of them; and there is nothing hid from its heat.” Again there are a number of important nuances here. Sungenis correctly noted that the Hebrew word מֹוצָאֹו (môtsâ’), which is translated “rising” in many English translations, doesn’t literally mean “rising” but more exactly “goes forth”. But he fails to note that even more so than with the word yâtsâ’, môtsâ’ conveys the specific nuance of going forth from a source or a starting point. The Brown-Driver-Briggs lexicon defines it as, “act or place of going out or forth, issue, export, source, spring.”

The “circuit” (וְּתְקוְּפָתֹו, teqûphâh) of the sun is said to be, as it were, from end to end of the heavens – a starting point and an ending point – that is, from one horizon to the other. Again, this is a metaphorical description of sunrise and sunset.

And finally the psalmist emphasizes the sun’s heat, which would confine his description to the daylight hours. All of these observations combine to highlight what’s obvious to all of the Old Testament commentators I referenced, namely, that this whole passage is a metaphorical/phenomenological description of sunrise and sunset. There aren’t any literal, physical details of the universe revealed here.

Now Sungenis countered this by contending that this passage actually represents a mix of phenomenological and literal language:

Apparently Mr. Palm fails to recognize that Scripture often mixes literal and metaphorical language together to convey a certain truth (“Response to David Palm on the Galileo Issue”, p. 41).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Sungenis doesn’t even attempt to lay out any principles by which he decides which parts of this (or any) poem are literal and which are metaphorical. But he applies this unsupported assertion to Psalm 19, with very humorous results. Within the space of just a few pages in Galileo Was Wrong he completely contradicts himself, assigning two mutually exclusive meanings to the same words.

Of the passage, “His going forth is from the end of the heaven, and his circuit unto the ends of it: and there is nothing hid from the heat,” Sungenis claims that there are only two ways that it can be taken:

The accuracy of the account can be noted in the fact that there are only two options for the sun to complete its course. Either it refers to the heliocentric view that believes the sun is traveling around the Milky Way galaxy, or it refers to the geocentric model in which the sun travels around the Earth. Of the two options, we are confined to the latter, since the word “circuit” refers to the time span of one year (GWW2, p. 71; my emphasis).

Did you catch that? He insists that this verse can only be addressing the sun’s movement over the course of a year, otherwise it makes no sense (apparently the much more obvious allusion of sunrise and sunset didn’t make it into consideration here.) And just for emphasis he repeats the assertion:

Only in the geocentric system wherein the sun travels around the Earth in the period of one year can the passage have any fulfillment and meaning. As it stands, the sun begins its year-long journey at one sign of the zodiac and completes it at the last sign. It is these two points that the Psalmist refers to when he says in vr. 6: “from the end of the heavens…to the end of them.” (GWW2, p. 71; my emphasis.)

And after some further discussion, Sungenis again insists that this is about the sun’s annual cycle:

Galileo, perhaps not familiar with the Hebrew of the Old Testament, seems unaware that the word “circuit” (verse 6: “and its circuit to the end of them”) refers to the space of one year as opposed to instantaneous emanation. In other words, the Psalmist insists that it takes the sun one year to complete its circuit (pp. 72f.; emphasis mine.)

And what leads him to reach this conclusion with such absolute certainty? He advances the claim that the word teqûphâh, which is translated in various English versions as “course” or “circuit”, “literally means ‘the revolution of the year’” (ibid., p. 71).

And what leads him to reach this conclusion with such absolute certainty? He advances the claim that the word teqûphâh, which is translated in various English versions as “course” or “circuit”, “literally means ‘the revolution of the year’” (ibid., p. 71).

The problem is that teqûphâh doesn’t mean any such thing. The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew lexicon presents the definition as, “coming round, circuit of time or space, a turning, circuit”. It can be used in the context of a “coming round” of a year, but it does not intrinsically or literally mean “the revolution of the year”. So Sungenis is abusing the Hebrew language in the service of his personal dogma, geocentrism. We’ll see more of that before this article is finished.

Further on, Sungenis repeats his claim yet again:

the Psalmist puts both the “rising or going forth” of the sun grammatically adjacent to its “circuit or orbit,” thus denoting that the “going forth” is the same as its circuit or orbit that transpires between the two end points, all of which takes place in one year (GWW2, p. 73; emphasis mine.)

So at least four times in GWW Sungenis insists that this verse of Psalm 19 refers to an annual circuit of the sun and only in that interpretation, to use his own words, “can the passage have any fulfillment and meaning.”

This is, of course, nonsense. It’s problematic enough for Sungenis that, as we have seen above, all of the contextual and linguistic indications in the text point to a metaphorical description of sunrise and sunset. But what’s particularly odd is that this is the position taken by none other than…….Sungenis himself. And he takes this contradictory position earlier, in the very same section of Galileo Was Wrong where he argues that it can only mean an annual solar cycle.

On page 70 of GWW2, Sungenis insists that in the very same verse of Psalm 19 that he contends must refer to the sun’s “year-long journey”, the psalmist refers instead to “the sun’s daily traverse (p. 70)” Lest you think I’m making this up or taking Sungenis out of context, here are his own words at length:

Psalm 19 first establishes in literal language that the sun moves around the earth every day by the statement in verse 6: “Its rising is from one end of the heavens, and its circuit to the other end of them.” In fact, the Psalmist uses five distinct words of movement to describe the sun’s daily traverse – one describing the background against which the sun moves (“set a tent for the sun”), and four describing the sun’s movement (“comes forth,” “runs its course,” “rising” and “circuit”) (GWW2, p. 70).

Notice again that he says on page 70 that the words translated as “going forth” and “circuit” are two of the five words that describe the sun’s “daily traverse”, but we’ve seen above that he says repeatedly on pages 71-73 that those same words refer to the sun’s annual cycle, a “circuit or orbit that transpires between the two end points, all of which takes place in one year” (p. 73).

And in his later “rebuttal” to me, he makes no explicit mention at all of this annual cycle, which in GWW2 he insisted was the only way to correctly interpret the text. The word that he insisted “literally means ‘the revolution of the year’”, is said to mean “orbit”:

R. Sungenis: First, I had already explained in my previous rebuttal to Mr. Palm (posted at www.galileowaswrong.com) that Scripture often uses a mixture of phenomenlogical [sic] (“tent”) and literal language (“orbit”), which is the case with Psalm 19:1-6. Second, and more pertinent to our discussion, Psalm 19:6 does not use the word “rising.” Again, “rising” is a word Mr. Palm’s English translation has used. The literal Hebrew reads: “From one end of the heavens is his going forth” from the Hebrew [Hebrew text], in which the word [Hebrew text] is “his going forth” not “his rising.” Again, the passage is speaking about movement from one side of the heaven to the other, not a vertical rising. This meaning is confirmed by the second half of Ps 19:6 “and his orbit to their ends.” The word “orbit” is the Hebrew [Hebrew text], which is from the root [Hebrew text] (“coming around,” “circuit,” “orbit”). Thus there is nothing phenomenological about this passage. It speaks precisely the same way as Joshua 10:13 (“Response to David Palm’s Essay ‘Pope Leo XIII on Literal Interpretation and the Unanimous Consent of the Fathers'”).

All explicit notion of an annual motion and a Hebrew word in verse 6 that means literally “the revolution of the year” is gone—but doesn’t he recall his own insistence in GWW that this was the “only” way the passage made any sense? Now he insists that it means the sun’s “orbit”. And according to Sungenis himself this “orbit” is “from one side of the heaven to the other”.

There are a number of problems here. The first is that teqûphâh does not mean “orbit”. Again, as defined in Brown-Driver-Briggs and as rendered in all English translations, it means “circuit” or “course” and in this specific context it describes the daytime “circuit” from end to end of the heavens, that is, from horizon to horizon.

Now Sungenis admits that this course is “from one side of the heaven to the other”, which sounds an awful lot like from horizon to horizon. Can he still be speaking here of the sun’s “year-long journey”? If so then Sungenis has an completely (and conveniently) distorted notion of what is meant by “literal”—even assuming a geocentric cosmos, it’s a gigantic stretch to call the sun’s annual motion with respect to the earth an “orbit” and even more of one to call it a “circle” as he says in GWW2. And the alleged annual solar motion certainly cannot be described as being literally “from one side of the heaven to the other”[i]. Sungenis’ convoluted interpretation is light years away from anything like taking this language “literally”.

Now Sungenis admits that this course is “from one side of the heaven to the other”, which sounds an awful lot like from horizon to horizon. Can he still be speaking here of the sun’s “year-long journey”? If so then Sungenis has an completely (and conveniently) distorted notion of what is meant by “literal”—even assuming a geocentric cosmos, it’s a gigantic stretch to call the sun’s annual motion with respect to the earth an “orbit” and even more of one to call it a “circle” as he says in GWW2. And the alleged annual solar motion certainly cannot be described as being literally “from one side of the heaven to the other”[i]. Sungenis’ convoluted interpretation is light years away from anything like taking this language “literally”.

Sungenis’s other argument is that the Hebrew word that’s commonly translated “rising” in the first sentence of v. 6 really means merely “goes forth”. But as we have already seen this doesn’t capture the actual nuance of the word, which has the sense of proceeding from a starting point. As Brown-Briggs-Driver has it: “act or place of going out or forth, issue, export, source, spring.” This nuance of a starting point is further bolstered by the rest of the verse, which speaks of the sun as starting from “one end of the heavens” and proceeding “to the other end of them.” This cannot be applied coherently to an “annual motion” of the sun. And neither can it be a literal description of the sun’s motion around the earth, as the geocentrist claims. If this is a literal description of the movement of the sun revolving around the earth then is it really the new geocentrist contention that a circle has an end? Did the biblical authors know some axiom of geometry that we don’t? The twin use of the term “end” demonstrates that this is all with reference to the horizon of the earth, that is, it’s phenomenological language from end to end.

But Sungenis piles on the absurdity, grasping at straws to trying and explain how this language of end to end can literally describe a circular path:

It is safe to say that neither Galileo nor few, if any, of his contemporaries would have known the actual grammar of the passage, which is somewhat deeper than what our English, or even the Latin, translations can afford us. Saving for the clause “and nothing is hid from its heat,” the grammatical structure of Psalm 19:6 [18:7] places “from the end” and “to their ends” at opposite poles of the main clause, and positions “his rising” and “his circuit” as one unit connected by a waw-consecutive, which is then placed between the two “end” points noted above. Because a circle has neither beginning nor end, the polarity of “from the end…to their ends” is the colloquial way to describe the dimensions of a circle. If it begins at the ending and ends at the ending, then it has no beginning or ending. It just continues, ad infinitum. Within this closed circle, the Psalmist puts both the “rising or going forth” of the sun grammatically adjacent to its “circuit or orbit,” thus denoting that the “going forth” is the same as its circuit or orbit that transpires between the two end points, all of which takes place in one year (GWW2, p. 73).

Do you follow that? If you don’t, you’re certainly not alone. Sungenis’ “literal” interpretation is that precisely because a circle has no end points, the “colloquial way” to describe a circle is to speak of its two end points. This claim is so absurd that one has to seriously question whether Sungenis himself actually believes this hogwash. I challenge Sungenis to provide the evidence from any ancient Hebrew source illustrating his claim that the phrase “from the end…to the end” is “the colloquial way to describe the dimensions of a circle.” I think it’s safe to say that this is yet another prime example of the kind of preposterous grammatical and exegetical gymnastics Sungenis is willing to employ under the guise of scholarly-sounding language in order to “prove” his case (see here and here for several other examples.)

But perhaps the most humorous example of Sungenis advancing complete nonsense with unshaken conviction is his mangling of the similes used in Psalm 19. Sungenis writes:

The purpose of these descriptions is not for mere cosmetic value. These metaphors portray the images of tremendous energy and movement. In fact, there are few images that better represent single-minded determination and vigor than a bridegroom who seeks his bride and an athlete running a race. Both have strong desire firmly in mind and no concern or obstacle can bar them from their appointed goal. One would have to cripple or kill them in order to stop them. So strong are these images that, if the sun did not actually move in a circuit each day, there would be little reason for the Psalmist to employ the metaphors (GWW2, p. 70; emphasis mine.)

That’s certainly some very forceful sounding argumentation, isn’t it? The first obvious problem is that the imagery of Psalm 19 refers to a bridegroom leaving his bride in the morning, not seeking her. So, correcting for Sungenis’s little error of spousal directionality, we’re led to believe that an in-depth examination of the Hebrew language here in Psalm 19 paints a picture of a bridegroom so incredibly motivated to get as far away as possible from his bride in the morning that “one would have to cripple or kill [him] in order to stop [him]”!

Perhaps in order to maintain his confident claim that this passage was intended to “portray the images of tremendous energy and movement”, Sungenis will appeal to the ancient tradition of arranged marriages and the use of the veil to hide the face of the bride? Maybe when the bridegroom of this psalm finally laid eyes on his bride in the light of morning he ran screaming for the hills?

Perhaps in order to maintain his confident claim that this passage was intended to “portray the images of tremendous energy and movement”, Sungenis will appeal to the ancient tradition of arranged marriages and the use of the veil to hide the face of the bride? Maybe when the bridegroom of this psalm finally laid eyes on his bride in the light of morning he ran screaming for the hills?

All joking aside, the point of employing the imagery of a bridegroom leaving his chamber in the morning is not to show “tremendous energy and movement” – as Sungenis insists for the sake of propping up geocentrism – but to convey an image of the morning sun appearing with joy and warmth, like a man arising in the morning after a night spent consummating nuptials with his beloved bride.

The second obvious problem with Sungenis’s interpretation is that the simile of an “athlete running a race” is a clear allusion to speed, to rapidity of motion. This harmonizes perfectly with the sun’s speedy “course” from horizon to horizon, but harmonizes very poorly indeed with the sun’s plodding “year-long journey” proposed by Sungenis.

Notice again that Sungenis speaks specifically of the sun’s course “each day”, in direct contradiction to his contention elsewhere that this verse must describe the sun’s “year-long journey”.

The idea that we can reach firm conclusions about scientific details of the universe by reading such a text looks increasingly ludicrous. And it gets even worse. In the same section of Galileo Was Wrong, Sungenis derives another blinding “scientific” observation from this poem by highlighting the psalmist’s statement that the sun radiates heat:

The addition of “there is nothing hid from its heat” is very significant, since it is a scientific fact that the sun radiates heat. Logically, one scientific fact deserves another. Hence, it follows that the sun’s movement must also be a scientific fact, since it would be rather inconsistent to treat one aspect of the sun scientifically and the other unscientifically (GWW2, p. 71).

Of course, this is another illustration of Sungenis’s penchant for employing non sequiturs. Remarkably, he weaves three completely unsupported speculations together in order to reach a “firm” conclusion. “One scientific fact deserves another” is supposed to pass for a serious, scholarly argument? Really? “Hence, it follows that the sun’s movement must also be a scientific fact”? Actually, no, it doesn’t necessarily follow (and I’ll address the other supposed “scientific fact” conveyed in this text about the sun’s heat below). And last, “it would be inconsistent to treat one aspect of the sun scientifically and the other unscientifically”. Probably true, if one were writing a science text. But not true if one were writing a poem – which is precisely what this particular text is.

Now, to the issue of the supposed “scientific” statement in Psalm 19 about the sun radiating heat, a little further on Sungenis himself generously shows how ridiculous it is to find scientifically precise details here when he takes Galileo to task for inserting some sort of physical details into the text:

Galileo then goes on to talk about the sunspots he has discovered that seem to indicate that the whole mass rotates. From this he theorizes that all the other celestial bodies rotate, including and especially the Earth. Unbeknownst to Galileo, astronomical science has revealed that only some of the planets rotate, and thus Bellarmine was, by our modern hindsight, correct in disallowing Galileo to make such an unqualified presumption (GWW2, p. 72).

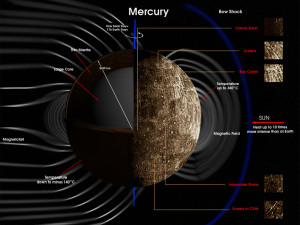

Sungenis didn’t notice that he’s walked into a buzz saw here. Of all things about which to chide Galileo, this is particularly ironic. First, Sungenis has his facts wrong—all of the planets in our solar system do rotate on their axes. It used to be thought that Mercury didn’t, but that has since been disproven (see Mercury: Orbit and Rotation). One would think that a guy who seeks to set the entire world of astrophysics straight could get his own basic facts about our own solar system right.

But even more ironically, it happens to be precisely the planet Mercury, which is closest to the sun, that has incredibly frigid temperatures on the dark side. So thoroughly hidden from the sun’s heat is that dark side that the temperatures can drop as low as -300°F. If you think that -300°F on the surface of the closest planet to the sun can be harmonized with a literal, scientific interpretation of the psalmist’s statement that, “there is nothing hid from its heat”, well then we have a pretty radically different view of what “scientific” and “literal” mean.

But even more ironically, it happens to be precisely the planet Mercury, which is closest to the sun, that has incredibly frigid temperatures on the dark side. So thoroughly hidden from the sun’s heat is that dark side that the temperatures can drop as low as -300°F. If you think that -300°F on the surface of the closest planet to the sun can be harmonized with a literal, scientific interpretation of the psalmist’s statement that, “there is nothing hid from its heat”, well then we have a pretty radically different view of what “scientific” and “literal” mean.

All of these observations point to one undeniable conclusion—this whole passage is a poetic description of sunrise and sunset, not a partially literal and scientific description of a physical motion of the sun around the earth. In the geocentric system is the sun’s “course” or “circuit” literally from horizon to horizon? No, in that system its “course” or “circuit” literally is a circular/elliptical orbit that has no end points. It is impossible to speak literally of the end points of a circle or ellipse. Once we speak of end points then even from the geocentric vantage we are unambiguously in the realm of phenomenological language. And if it’s only the language of appearances then it cannot be claimed to contribute any concrete knowledge about actual, physical motion.

The sun cannot move from “end to end” in a circular orbit around the earth because a circular orbit has no ends—in a “literal” geocentric view of things this passage results in nonsense. Only when taking this language as phenomenological—as a metaphorical description of the appearance of the sun’s course from horizon to horizon—does the passage make sense. The more Sungenis presses the text for literal, scientific details of the universe, the more ridiculous the exercise gets. [Update 05/14/14: Further down in GWW, Sungenis admitted that “ends”, “refers to the respective east and west horizons” and included Psa 19:4-6 as one of the passage where that is the case (see GWW3, 9th ed., p. 123.)]

And the fact is that there’s no point to Sungenis’ ridiculous exercise because this passage perfectly fits Pope Leo XIII’s dictum in Providentissimus Deus §18, namely, that:

the Holy Ghost “Who spoke by them [the authors of Scripture], did not intend to teach men these things (that is to say, the essential nature of the things of the visible universe), things in no way profitable unto salvation.” Hence they did not seek to penetrate the secrets of nature, but rather described and dealt with things in more or less figurative language, or in terms which were commonly used at the time, and which in many instances are in daily use at this day, even by the most eminent men of science. Ordinary speech primarily and properly describes what comes under the senses; and somewhat in the same way the sacred writers-as the Angelic Doctor also reminds us – `went by what sensibly appeared,” or put down what God, speaking to men, signified, in the way men could understand and were accustomed to.

Sungenis’ whole abortive “exegetical” enterprise makes it clear how inappropriate and futile it is to try and glean literal, scientific details from a poem. But there is, however, one statement of Sungenis’s on this passage with which I agree entirely – his contention that Psalm 19, “speaks precisely the same way as Joshua 10:13”.

I heartily agree. Old Testament scholars are unanimous in affirming that the specific description of the miracle of the sun and moon in Joshua 10:13 is first cast in Hebrew poetry. This strongly suggests from the outset that it’s dubious to try and glean scientific details of the motion of cosmological bodies from this passage. What’s more, as Old Testament scholar E. Power has pointed out, the word bô’ (בּוֹא , “enter”) in the latter prosaic section of verse 13 “always means ‘set’ when used of the sun” (A Catholic Commentary on Holy Scripture, p. 285; see Gen 15:12, 17; 28:11; Exod 17:12; Exod 22:26; Lev 22:7; Deut 24:13, 15; Jos 10:13; Judg 14:18; Judg 19:14; 2 Sam 2:24; 3:35; Ecc 1:5; Isa 60:20; Jer 15:9 (figuratively); Amo 8:9; Mic 3:6 (figuratively). Brown-Driver-Briggs defines the word thus, “of sun, set (go in, enter . . . opposed to יצא go forth, rise)” (my emphasis). This highlights the phenomenological nature of this language. In English we speak of the sun “rising” and “setting”. The ancient Hebrew in both prose and poetry spoke of the sun “going forth” and “going in”. But “rising”, “setting”, “going forth” and “going in” with respect to what? With respect to the horizon, of course. And again, once the horizon is the frame of reference for a description of the sun’s course the geocentrist cannot insist that it describes literal astronomical motions, for even in their own system they would have to admit that the sun does not literally “go forth” from one horizon and “go in” to the other in its continuous orbit around the Earth. As Sungenis himself has admitted, “The geocentrist knows that the sun ‘rises’ or ‘sets’ only with respect to the Earth’s horizon, and therefore, reference to a ‘rising sun’ in Scripture is just as phenomenal in the geocentric system as it is in the heliocentric” (GWW1, p. 226; emphasis mine). Well the same exact thing may be said about the Hebrew idiom of speaking of the sun “going forth” and “going in”, which also is clearly, “with respect to the Earth’s horizon”. This is phenomenological language and as Pope Leo XIII insists, the Holy Spirit did not intend to teach anything about the “essential nature of the things of the physical universe” through the use of such phenomenological language.

I heartily agree. Old Testament scholars are unanimous in affirming that the specific description of the miracle of the sun and moon in Joshua 10:13 is first cast in Hebrew poetry. This strongly suggests from the outset that it’s dubious to try and glean scientific details of the motion of cosmological bodies from this passage. What’s more, as Old Testament scholar E. Power has pointed out, the word bô’ (בּוֹא , “enter”) in the latter prosaic section of verse 13 “always means ‘set’ when used of the sun” (A Catholic Commentary on Holy Scripture, p. 285; see Gen 15:12, 17; 28:11; Exod 17:12; Exod 22:26; Lev 22:7; Deut 24:13, 15; Jos 10:13; Judg 14:18; Judg 19:14; 2 Sam 2:24; 3:35; Ecc 1:5; Isa 60:20; Jer 15:9 (figuratively); Amo 8:9; Mic 3:6 (figuratively). Brown-Driver-Briggs defines the word thus, “of sun, set (go in, enter . . . opposed to יצא go forth, rise)” (my emphasis). This highlights the phenomenological nature of this language. In English we speak of the sun “rising” and “setting”. The ancient Hebrew in both prose and poetry spoke of the sun “going forth” and “going in”. But “rising”, “setting”, “going forth” and “going in” with respect to what? With respect to the horizon, of course. And again, once the horizon is the frame of reference for a description of the sun’s course the geocentrist cannot insist that it describes literal astronomical motions, for even in their own system they would have to admit that the sun does not literally “go forth” from one horizon and “go in” to the other in its continuous orbit around the Earth. As Sungenis himself has admitted, “The geocentrist knows that the sun ‘rises’ or ‘sets’ only with respect to the Earth’s horizon, and therefore, reference to a ‘rising sun’ in Scripture is just as phenomenal in the geocentric system as it is in the heliocentric” (GWW1, p. 226; emphasis mine). Well the same exact thing may be said about the Hebrew idiom of speaking of the sun “going forth” and “going in”, which also is clearly, “with respect to the Earth’s horizon”. This is phenomenological language and as Pope Leo XIII insists, the Holy Spirit did not intend to teach anything about the “essential nature of the things of the physical universe” through the use of such phenomenological language.

The geocentrists would respond to this observation, I think, with a counter-assertion that the Fathers of the Church are unanimous in seeing just such cosmological details in this passage. Therefore, Catholics should be bound to such an interpretation.

But I’ve laid out in detail in “Geocentrism and the Unanimous Consent of the Fathers” that the Fathers don’t ever present geocentrism as a matter of divine faith. I would further point out, more specifically, that when the Fathers do allude to the miracle of Joshua 10, they don’t delve into physical details—they don’t say “how” the miracle happened. They do see it as a miraculous, heavenly portent, yes. But it’s usually commented upon to make a broader theological point, not to reveal the scientific make-up of the cosmos. Unlike the new geocentrists, the Fathers don’t extrapolate to a precise scientific point, from there jump to broad conclusions about a detailed cosmological system, and then treat this physical system they imagined as a dogma of the faith. [For more details on Joshua 10, please see “Sungenis Looses What He Has Bound on Joshua 10”.]

We must also keep firmly in mind that Pope Leo XIII, in Providentissimus Deus §18, stated with magisterial authority that the Holy Spirit did not put any such details of the physical universe into sacred Scripture. It should be obvious that even the Fathers of the Church can’t glean from Scripture what the Church teaches that the Holy Spirit never put there in the first place.

We must also keep firmly in mind that Pope Leo XIII, in Providentissimus Deus §18, stated with magisterial authority that the Holy Spirit did not put any such details of the physical universe into sacred Scripture. It should be obvious that even the Fathers of the Church can’t glean from Scripture what the Church teaches that the Holy Spirit never put there in the first place.

Also recall that Pope Leo clearly taught that in issues which the Fathers don’t lay down as matters of faith—tellingly the Pope speaks specifically of passages where “physical matters occur”—they may be speaking of ideas commonly held in their own times but which were subsequently found to be incorrect. Again, I’ve demonstrated that the Fathers do not lay out geocentrism as a matter of faith and give every indication that it was for them a matter of natural philosophy (see “Geocentrism and the Unanimous Consent of the Fathers”). Thus, according to the Magisterium, Catholics are free to hold divergent opinions on these “physical matters”:

The unshrinking defence of the Holy Scripture, however, does not require that we should equally uphold all the opinions which each of the Fathers or the more recent interpreters have put forth in explaining it; for it may be that, in commenting on passages where physical matters occur, they have sometimes expressed the ideas of their own times, and thus made statements which in these days have been abandoned as incorrect. Hence, in their interpretations, we must carefully note what they lay down as belonging to faith, or as intimately connected with faith-what they are unanimous in. For “in those things which do not come under the obligation of faith, the Saints were at liberty to hold divergent opinions, just as we ourselves are” (Providentissimus Deus §19).

Pope Leo also states that,

he [the exegete] must not on that account consider that it is forbidden, when just cause exists, to push inquiry and exposition beyond what the Fathers have done; provided he carefully observes the rule so wisely laid down by St. Augustine-not to depart from the literal and obvious sense, except only where reason makes it untenable or necessity requires (ibid. §15).

The degree of special pleading necessary to maintain geocentrism as a scientific view, coupled with the broadly recognized fact that the main passage in question in Joshua 10:13 is Hebrew poetry, renders the geocentrist attempt to mine the Scriptures for scientific support both unreasonable and futile. As Catholics, we should feel completely comfortable seeing in Joshua 10 the description of a genuine miracle, while at the same time leaving the precise physical details behind that miracle as an open question.

Conclusion:

Geocentrist Bob Sungenis insists that sacred Scripture—by his own admission, primarily the poetic psalms—contains all sorts of scientifically accurate details concerning matters of cosmology. From a distinctively Catholic perspective this assertion is particularly problematic and unreasonable because it runs directly contrary to the solemn teaching of the Magisterium (most notably in the encyclicals Providentissimus Deus by Leo XIII and Divino Afflante Spiritu by Pius XII). As we’ve seen in this article, Sungenis’s whole attempt is abortive. Applying such an over-literal hermeneutic to passages of poetry results in contradictions, incoherencies, and nonsensical conclusions. But when he has an ideological agenda, his objectivity just goes out the window.

The new geocentrists have attempted to persuade their readers of the truth of geocentrism on the basis of the Magisterium, the Bible, the Fathers, and science. The attempt is futile. The Magisterium of the Catholic Church does not now and never has taught any cosmological system as a matter of faith. The Bible, rightly interpreted, just doesn’t contain such details of the physical universe. The Fathers of the Church don’t present geocentrism as a matter of divine faith. And the scientific “case” for geocentrism is a massive exercise in special pleading, gummed together with conspiracy theories.

So, once again, Catholics are ultimately left to choose between following Sungenis and the new geocentrists or following the Catholic Church.

End Notes

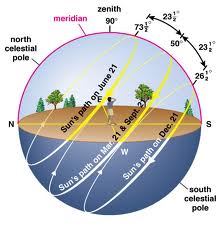

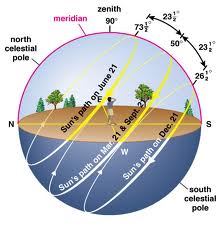

[i] A little reflection upon the sun’s apparent motion even in its annual cycle makes Sungenis’ interpretation all the more untenable. It is precisely the case that as the year progresses the sun appears to move higher on its daily course, then trends lower again, then back higher. So, exactly contrary to Sungenis’ contention, it is a “vertical rising” even in the case of the annual cycle. So even if this passage harmonizes with his weird contention that these words describe an annual cycle, Sungenis has blundered in his interpretation

[i] A little reflection upon the sun’s apparent motion even in its annual cycle makes Sungenis’ interpretation all the more untenable. It is precisely the case that as the year progresses the sun appears to move higher on its daily course, then trends lower again, then back higher. So, exactly contrary to Sungenis’ contention, it is a “vertical rising” even in the case of the annual cycle. So even if this passage harmonizes with his weird contention that these words describe an annual cycle, Sungenis has blundered in his interpretation

But more importantly, it’s just not reasonable to apply the word “orbit”, much less “circle” (both of which he uses, the latter in GWW2) to describe the sun’s annual (apparent) motion. A complex wobbly spiral would be more accurate. It’s a huge stretch to apply “orbit” or “circle” to such a path and the attempt puts us very far away from “literal” language.

Frankly, I think that on some level Sungenis knows this. I think this is precisely why he’s argued so hard that this is an annual cycle and not the more obvious “motion” of the sun from horizon to horizon. I think he knows that if he admits that the “ends” are the horizons then he’s lost the game. The only “motion” of the sun that takes place “from one side of the heaven to the other” is from horizon to horizon. But in the geocentric system is the sun’s “course” or “circuit” literally from horizon to horizon? No, in that system its “course” or “circuit” literally is a circular/elliptical orbit that has no end points. It is impossible to speak literally of the endpoints of a circle or ellipse. Once we speak of end points then even from the geocentric vantage we are unambiguously in the realm of phenomenological language. And if it’s only the language of appearances then it cannot be claimed to contribute any concrete knowledge about actual, physical motion. Checkmate.

So he has to come up with some other “ends” that physically fit his system, no matter how ridiculous the exercise.