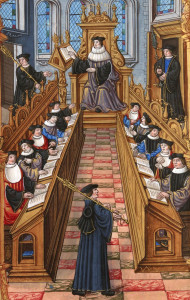

Finally, the new geocentrists point out that the 1633 decree against Galileo was disseminated throughout the Church and from this fact they argue that geocentrism continues to have standing as an established doctrine in the Catholic Church. Sungenis has argued this in the most detail. He cites Dorothy Stimson to the effect that:

Finally, the new geocentrists point out that the 1633 decree against Galileo was disseminated throughout the Church and from this fact they argue that geocentrism continues to have standing as an established doctrine in the Catholic Church. Sungenis has argued this in the most detail. He cites Dorothy Stimson to the effect that:

Pope Urban had no intention of concealing Galileo’s abjuration and sentence. Instead, he ordered copies of both to be sent to all inquisitors and papal nuncios that they might notify all their clergy and especially all the professors of mathematics and philosophy within their districts…” (The Gradual Acceptance of the Copernican Theory of the Universe, 1917, pp. 67-68)

[Pope] Urban upheld the 1616 Sacred Congregation’s verdict of “formal heresy” for Copernicanism and “vehemently suspect of heresy” for Galileo after obtaining Galileo’s renunciation in 1633. He sent notice of the condemnation to all the inquisitors and papal nuncios of Europe, making it an official proclamation of the Vatican. (GWW2, 34).

The magisterium’s actions were unprecedented. From this evidence one could argue that such pervasive and regimented procedures were at least reasonably close to the criteria required for a binding and irreformable teaching (GWW2, 278).In fact, the Church’s historic teaching on geocentrism and her condemnation of heliocentrism fulfills all the criteria of Lumen Gentium 25 . . . During the condemnations against heliocentrism the Church issued some of the most detailed and comprehensive decrees ever written. Every wrinkle of the issue was investigated, arguments were presented and rebutted, witnesses were put under oath, experts were called in for testimony, the most severe and condemnatory language was formulated in the final decree, that is, that heliocentrism was “formally heretical” and “erroneous in faith.” If geocentric doctrine does not qualify under the rubrics of Lumen Gentium 25, what does? (GWW2, 281).

Undoubtedly Pope Paul V. wished the decree made and privately instigated it, as Urban VIII. did the sentence against Galileo; and in this sense the former may be attributed to the one and the latter to the other, and the condemnation of the Copernican theory to both. But in this they acted as private persons, and as such they were not (nor would they now be), according to theological rules, “infallible.” The conditions which would have made the decree of the Congregation, or the sentence against Galileo, of dogmatic importance, were, as we have seen, wholly wanting. Both Popes had been too cautious to endanger this highest privilege of the papacy by involving their infallible authority in the decision of a scientific controversy; they therefore refrained from conferring their sanction, as heads of the Roman Catholic Church, on the measures taken, at their instigation, by the Congregation “to suppress the doctrine of the revolution of the earth.” Thanks to this sagacious foresight, Roman Catholic posterity can say to this day, that Paul V. and Urban VIII. were in error “as men” about the Copernican system, but not “as Popes.” (Karl von Gebler, Galileo Galilei and the Roman Curia, trans. J. Sturge, London: C. Kegan Paul & Co., 1879, pp. 235-6)